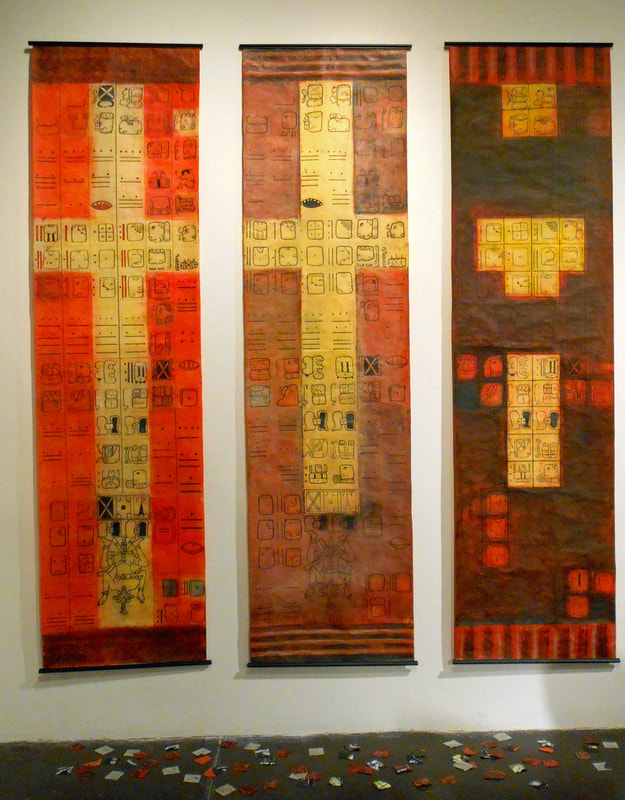

“Erased” is a scroll triptych created for "Banned," an invited exhibition about censorship. The work was exhibited in 2016 at the Santa Fe Community Gallery. It references one of the most egregious historical acts of censorship, the July 12, 1562 burning of the Mayan codices by Friar Diego de Landa (1524 - 1579). The codices were written in Maya hieroglyphic script on bark paper and recorded more than 800years of Mayan history and culture. The paper was made from the inner lining of fig trees indigenous to the area. It was gessoed with a fine plaster and the writing was done with small brushes, probably made from animal hair. One of the colors used was what is now known as “Mayan blue.” It is similar to indigo, but the interesting thing about it is that it contains elements not native to the area where the codices were written, particularly a certain kind of clay.

In his Report of Things in Yucatán, here’s how de Landa described his own actions: "These people (the Maya) used certain letters with which they wrote in their books about ancient subjects...We found many books written with these letters and since they held nothing that was not falsehood and the work of the evil one, we burned them all, which they regretted to an amazing degree, and which caused them much affliction.” Three codices survived and are now known by the name of the cities whose museums possess them: the Dresden Codex, considered the most complete, the Madrid Codex and the Paris Codex. They offer but a glimpse of the Mayan culture and ritual that must have been recorded in the censored writings.

The “Erased” triptych is based on a page from the Dresden Codex. Panel one records the visual beauty of the Mayan language. Successive panels two and three reference itsimagined destruction through de Landa’s act of censorship. The darkening of the surfaces represents the onslaught of smoke and fire. The final panel is charred and only a few glyphs remain visible. The shards on the gallery floor beneath the scrolls represent lost knowledge. The cross imagery is self explanatory.

Mette Newth, writing in The Long History of Censorship states: “Without a doubt, the Inquisition’s censorship in the colonies of the Americas was oppressive and sinister. Nevertheless, it could hardly compare to the Spanish invaders’ destruction of the unique literature of the Maya people. The burning of the Maya Codices...remains one of the worst criminal acts committed against a people and their cultural heritage, and a terrible loss to the world heritage of literature and language.” Unfortunately, such acts continue in our time, such as the recent destruction of world heritage sites, including libraries.

Today, the surviving Mayan codices are revered. Whole societies of scholars have developed to study and decipher them. Many scholarly papers and books have been written about them. Nonetheless, the surviving codices represent a fraction of what wecould have known and appreciated about the Maya.

As for the Friar, his legacy is also mixed. After burning the codices, he was chastised by the Catholic church and returned to Spain. While awaiting trial, he wrote a detailed description of the very culture his actions had helped destroy: “Relacion de las cosas de Yucatán,” a resource of great interest to the same scholars who condemn his act of censorship. He was subsequently made a bishop and sent back to Yucatán.

In his Report of Things in Yucatán, here’s how de Landa described his own actions: "These people (the Maya) used certain letters with which they wrote in their books about ancient subjects...We found many books written with these letters and since they held nothing that was not falsehood and the work of the evil one, we burned them all, which they regretted to an amazing degree, and which caused them much affliction.” Three codices survived and are now known by the name of the cities whose museums possess them: the Dresden Codex, considered the most complete, the Madrid Codex and the Paris Codex. They offer but a glimpse of the Mayan culture and ritual that must have been recorded in the censored writings.

The “Erased” triptych is based on a page from the Dresden Codex. Panel one records the visual beauty of the Mayan language. Successive panels two and three reference itsimagined destruction through de Landa’s act of censorship. The darkening of the surfaces represents the onslaught of smoke and fire. The final panel is charred and only a few glyphs remain visible. The shards on the gallery floor beneath the scrolls represent lost knowledge. The cross imagery is self explanatory.

Mette Newth, writing in The Long History of Censorship states: “Without a doubt, the Inquisition’s censorship in the colonies of the Americas was oppressive and sinister. Nevertheless, it could hardly compare to the Spanish invaders’ destruction of the unique literature of the Maya people. The burning of the Maya Codices...remains one of the worst criminal acts committed against a people and their cultural heritage, and a terrible loss to the world heritage of literature and language.” Unfortunately, such acts continue in our time, such as the recent destruction of world heritage sites, including libraries.

Today, the surviving Mayan codices are revered. Whole societies of scholars have developed to study and decipher them. Many scholarly papers and books have been written about them. Nonetheless, the surviving codices represent a fraction of what wecould have known and appreciated about the Maya.

As for the Friar, his legacy is also mixed. After burning the codices, he was chastised by the Catholic church and returned to Spain. While awaiting trial, he wrote a detailed description of the very culture his actions had helped destroy: “Relacion de las cosas de Yucatán,” a resource of great interest to the same scholars who condemn his act of censorship. He was subsequently made a bishop and sent back to Yucatán.